Welcome back to my ongoing series exploring how space settlement is portrayed in the stories we tell. So far, I’ve discussed books, TV shows, movies, even board games, but this month it’s time to dive in to the world of video games: specifically, the enormously popular and addictive competitive strategy game Sid Meier’s Civilization VI, aka Civ VI.

“But wait!” I hear [some of] you say, “Civ VI isn’t about space settlement! It’s set on Earth!”

Hmm, sounds like someone hasn’t achieved the Science Victory in a game of Civ VI and launched a spacecraft to Mars.

But no, it’s true, Civ VI isn’t explicitly about space settlement. However, it is a classic example of a genre of games that happens to illustrate a key ideology present in today’s space settlement advocacy: so-called “4X games”.

The Four Xs of Civilization

Coined by game writer Alan Emrich in 1993, a game in this genre “features the essential four X's of any good strategic conquest game: EXplore, EXpand, EXploit and EXterminate.” In 2016’s Civ VI, players start on a shared map of the world, each dropped in a random position with a single fighting unit and a “Settler” capable of creating a new city. Cities can create new units, research new technologies, expand over time, and build districts to generate more resources. Units can be used to explore the map, revealing harvestable resources, sites for new cities, and the locations of neighboring civilizations. Players create their own stories, their own histories, as their civilization grows and thrives (or not) under their care.

Civ VI allows players to win the game in several different ways: by conquering the capital cities of all other civilizations by force, converting all civilizations to the winner’s religion, attracting more foreign tourists than any other civlization’s domestic tourists, or establishing a colony on Mars. This last type of victory, a “Science Victory,” changes slightly in the Gathering Storm expansion pack, which requires the winner to launch an expedition towards an exoplanet, where presumably the 4X process will start all over again.

There are a number of 4X games set in multi-planet empires— Master of Orion, Galactic Civilizations, Sins of a Solar Empire, Stellaris— but I wanted to focus on the terrestrial Civ VI for this series for a couple of reasons. First, I’m especially fascinated by the stories we tell about the early days of space settlement: no aliens, no fantastical technologies, no breaking the laws of physics. (But don’t worry, if you’re more interested in those themes, I did write about Star Trek earlier this year.)

Second, while a game of Civ VI ends before the player gets the chance to explore or exploit another planet, it still does an excellent job of showing why so many people look towards space with those four Xs in mind: because that’s how so many people look at our history here on Earth. The expansion of territory, sometimes through violence, in order to find and extract more and more resources, is considered by many people in Western nations— including within the space settlement advocacy community— to be the natural, obvious, and obviously correct approach to running a real-world civilization. So it’s no surprise that many space settlement advocates project that same 4X worldview onto new worlds.

The “History” of Civilization

But what am I saying here? Am I arguing that 4X games like Civ VI encourage this colonialist worldview, influencing players to be more supportive of extractivist, expansionist ideologies? No— but I do think these games are attractive and addictive to play for the same reason that so many space settlement advocates have extractivist plans for space. As Dan Olson notes in his excellent video on “Minecraft, Sandboxes, and Colonialism”: “I like terraforming and building big things, in part because I was raised in a culture that values terraforming and building big things. A culture that looks at the New York skyline, the Hoover Dam, and the Trans-Canada Highway and sees, first and foremost, progress. A culture that sees these things as good.”

I’m generally not a fan of trying to apply armchair evolutionary psychology to explain ideology, but it’s not a stretch to say that there are probably same basic biological instincts at play here. By rewarding a player’s exploration of the game map with the discovery of rare, valuable resources, Civ VI is harnessing the same neurochemistry that incentivizes human to forage for food. But players are also coming to the game with a cultural framework for their motives, specifically the colonialist mindset that many of us were raised in, and which runs through much of today’s space settlement advocacy: Those unclaimed parts of the map aren’t just locations where we might find resources, they’re raw materials in themselves, waiting to be improved, to be made productive, to be civilized. Whether it comes from a belief in Manifest Destiny or the literal instructions of a video game, this way of looking at a planet’s surface urges us to spread, gobbling up territory until we bump up against the border of our competitors doing the same.

Civ VI directly references real-world history by naming its civilizations, cities, and playable leaders after actual places and people, but it’s been criticized for its shallowness. In particular, the game starts all players at the same level, randomly scattered across an empty (except for some non-player “barbarians”), resource-rich planet, more like popular visions of space colonization than the way human societies have actually emerged and interacted. Look, this is a video game, not a history textbook: it’s meant as entertainment, not education. But I think one of the reasons Civ VI is so popular is that it provides such a simple, straightfoward model of our unpleasantly complicated world, suggesting that all that’s necessary to “win” (conquer) the world is the right strategy and a little luck in your starting position.

After the Victory

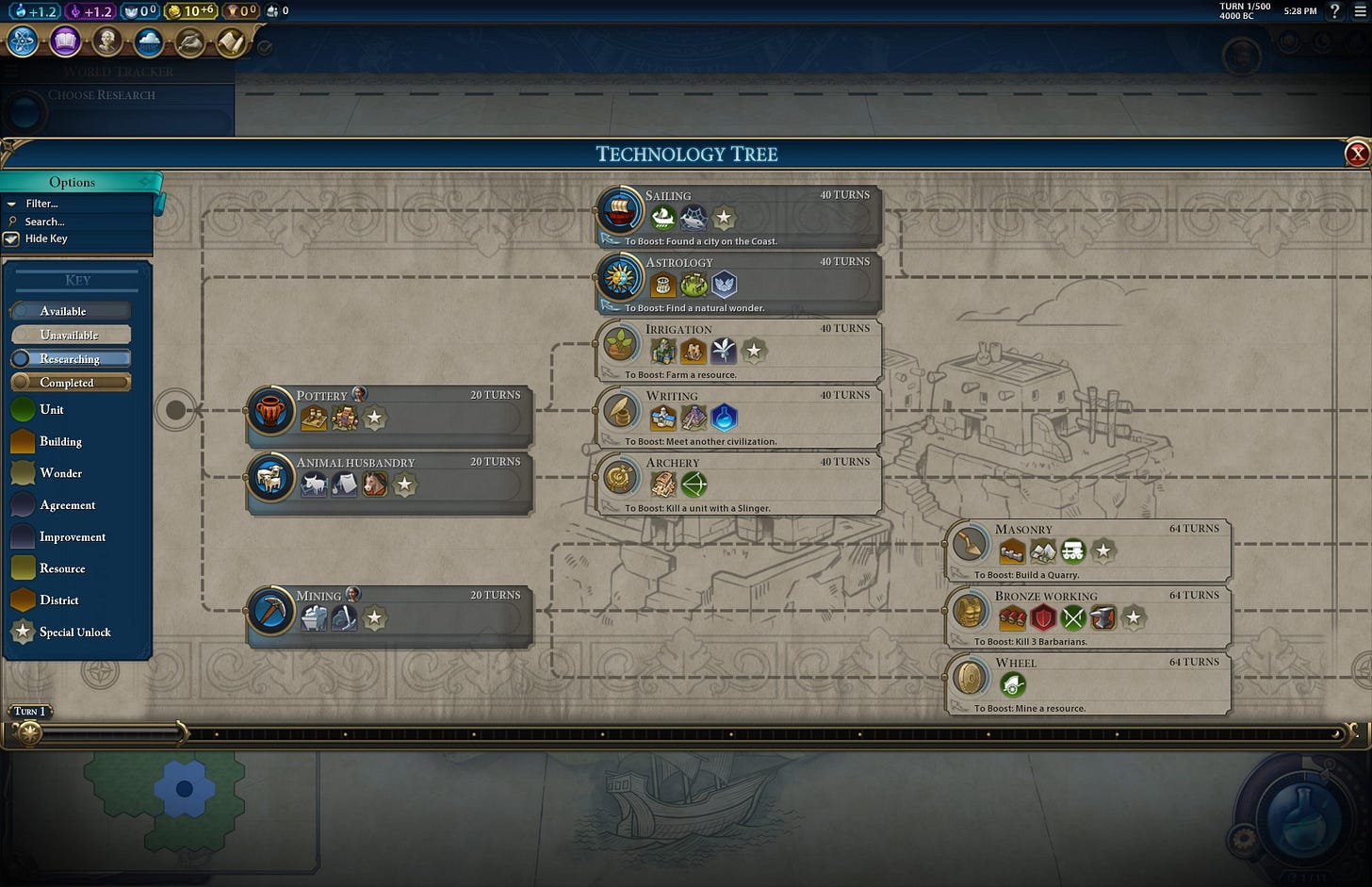

Of course, the real world is not so simple. In the game, progress is linear— the technology “tree” that players move along as they conduct research is shaped more like a single branch with a few twigs. The progress of each player towards each possible victory condition is easily quantified and ranked. At any point in time, it’s obvious to all players which civilizations are objectively better than other. Cultural diversity provides no mechanical reward; the only benefit of the arts is to generate tourism. Again, I’m not arguing that a video game owes us more complexity; I’m pointing out that this is how some people see the world in real life.

By the time a player has amassed enough research and productivity to reach the Science Victory conditions, every inch of the game’s map— the planet— is usually covered by borders, building, mines, and farms. It’s used up, filled to the brim. The rising ocean has eaten into unprotected coastal territories, thanks to the simulated climate change effects triggered when players pass through the coal and oil eras of the tech tree. Perhaps the various civilizations’ military, cultural, and religious forces have reach an equilibrium; perhaps war is on the verge of breaking out. But with no territory left to explore and no new resources to exploit, there’s only one direction to expand towards: straight up. A rocket streaks upwards from a launch site. The game congratulates you, then asks if you’d like to start again, on a fresh and empty map.

But in real life, while a handful of humans may get access to a new, less hospitable map far away, the crowded civilizations left on Earth will need to keep going. They will need to ask: What are we when we’re not expanding and exploiting? I refuse to believe that our species is simply a virus, with a sole purpose to reproduce ourselves and spread to new host planets. So what are our values and goals outside the four Xs? What’s a civilization for?

Games aren’t responsible for answering these questions, but we are. And we might as well start now, on this real-world map where we get to define our own win conditions.