Let’s kick off this series on space settlement science fiction with an easy one: Star Trek, a series of television shows that premiered before the Apollo 11 moon landing and is still in production today. As a franchise, Star Trek has expanded beyond television into films, novels, video games, and more, but I would argue that the first few TV series had the biggest cultural influence on our ideas about humanity’s future in space. It’s had such a large impact, in fact, that I don’t know that I need to spend a lot of time summarizing the story here. But to get myself in the habit: Star Trek imagines a distant future in which humans have invented faster-than-light travel, made first contact with several alien species, settled other worlds, and formed an interspecies government, the United Federation of Planets, with an exploration-focused armada of spaceships called Starfleet. Each show tends to focus on the crew of a single ship or space station, exploring the galaxy and dealing with interspecies conflicts.

Star Trek and Space Settlement Ethics

Star Trek is set at the opposite end of space settlement from where we sit today: for the characters, space has already been settled, and part of the entertainment and adventure comes from their exploration of all the various and interesting ways people have built communities in space. In fact, most of the characters do not live on settled planets but rather on spacecraft traveling the galaxy. So despite the technological advancements and civilization expansion that has taken place, the characters are able to spend much of their time at the edge of the unknown (to the Federation): the “frontier”.

The franchise’s metaphor of space as the “final frontier” is directly connected to America’s cultural obsession with the mythology of the “Wild West” and the European colonization of North America. The very first Star Trek series premiered at a time when television Westerns were extremely popular, and was famously pitched by creator Gene Roddenberry as a “Wagon Train to the stars”, referencing a top-rated Western TV show of the late 1950s and ‘60s. But the characters on Star Trek are rarely seeking new land or resources for territorial expansion and colonization; instead, they’re “seek[ing] out new life and new civilizations”, making first contact with indigenous species but prioritizing their agency and self-determination. In fact, the protagonists in the Star Trek universe have an explicit rule against interfering with other societies, their Prime Directive.

Like most science fiction, the writers use Star Trek to comment on our current world, drawing parallels between fictional alien species and the various forces that shape our own society. Even the Star Trek episodes that focus more heavily on sci-fi technology (and the various ways it can go wrong) are ultimately about the reactions and choices of the characters. For me, this is exactly why science fiction like Star Trek is such an interesting way to explore questions about space settlement ethics: these stories aren’t about the feasibility of a given technology, but about asking how a hypothetical technology should be used, and what effects it might have on the people living with it.

One of the major reasons why Star Trek is so enjoyable to watch, especially in the face of all the (excellent, but) dystopian science fiction in the world, is its optimistic approach to the future. The protagonists’ society and institutions— Starfleet, the United Federation of Planets, etc.— prioritize peaceful exploration. Not because the characters are intrinsically peaceful: the fictional history of Star Trek’s humankind, other alien allies, and the Federation as a whole includes a lot of poverty, oppression, and war. But these groups have done the work to improve themselves and emerge as a society structured around altruistic values. Conflict still exists in Star Trek’s future (that’s what makes it a good story), because conflict will always exist, but that doesn’t dissuade the protagonists from trying to find the best way forward according to their values. It’s a hopeful and refreshing kind of escapism.

The Mirror Universe: Star Trek’s Dystopia

But as I’ve been revisiting Star Trek these past few weeks in preparation for writing this post, I’ve found myself thinking less about the utopian aspects of its fictional world and more about its presentation of a dystopia. Not any of the cautionary-tale, single-episode alien societies encountered by our heroes, but Star Trek’s dystopian vision of humanity itself, seen in episodes set in the “Mirror Universe”.

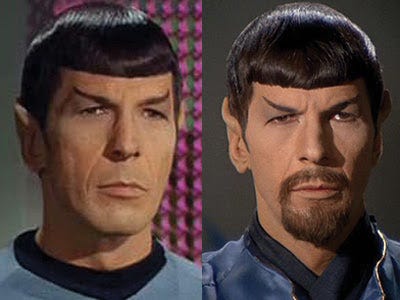

First seen in the episode “Mirror, Mirror” in the first Star Trek series, the Mirror Universe represents one of science fiction’s favorite tropes: an alternate dimension in which most of the characters and settings still exist, but are… different. In the Mirror Universe, rather than joining with other alien species to form the United Federation of Planets, humans formed the cruel and oppressive Terran Empire, enslaving other species and clashing violently with other civilizations. If you’ve ever seen the cliché in which a goatee represents the “evil” version of a normally beardless character, this comes straight from evil Spock in “Mirror, Mirror”:

Both of Star Trek’s versions of humanity— in the normal Star Trek universe, and in the Mirror Universe— have settled space and developed extremely advanced technologies along the way, like faster-than-light travel, instantaneous transporters, food replicators, and more. The suggestion, then, is that it’s not space settlement that made the Federation a good and healthy society. It’s their values: a love of diversity, an emphasis on diplomacy over violence, the prioritization of equitable distribution of resources. Humans in the Mirror Universe’s Terran Empire have all the same technology and resources, but that doesn’t make them better people. It just makes it easier for them to oppress others.

What can we learn from Star Trek?

It’s not hard to figure out why I’ve been thinking about this aspect of Star Trek in particular, lately. As the U.S. has struggled with the chaos and cruelty of Trump’s second term, I’ve been disappointed to see a mood of celebration in parts of the space industry and the space settlement advocacy community. For example, I recently watched a SpaceNews webinar on “Trump 2.0” that was advertised by at least one panelist, Michelle Hanlon, as a discussion of how they’re “hugely optimistic about space” under the new White House administration. Some U.S. space advocates, including speakers at this webinar, appear to be excited about having a president who is clearly being influenced by a major proponent of human space settlement (Elon Musk), which they see as a significant improvement over past administrations who haven’t prioritized space at all. People who worry about the U.S. falling behind in the current international scramble for space, and those who advocate for settling space as quickly as possible, see this as good news.

But at what cost? If we want a future like Star Trek, inventing warp drives and building bases on the Moon and/or Mars are only part of the story. We have to decide how we will use the technologies we’ll develop for space (not to mention the technologies we already have now)— What values will they serve and perpetuate in future generations? What parts of our history and present will we carry with us into space? If we expand our civilization beyond this planet but continue to exploit and harm each other and our environment, what have we accomplished?

Fortunately, this is a false dichotomy. We are not, in fact, faced with the choice between “space exploration, but through Trump” and “no space exploration at all”. For one thing, as we saw in Trump’s first term and are seeing again now, having a president who uses the phrase “Manifest Destiny in space” in speeches is not the same as having a president who will actually enable advancements in space— or science and technology in general. In just the first couple weeks of this second term, Trump’s administration has frozen funding for scientific research and frightened institutions into eliminating programs for recruiting underrepresented students to space science. How is refusing to fund science and shrinking the pool of potential future scientists good for space exploration?

I understand that space scientists, policymakers, and entrepreneurs will all have to figure out how their work can continue through the next four years of the current administration. After all, most plans for space science and exploration exist on a longer timescale than any single presidential term. But I don’t see any of the current political situation as an “opportunity” for people excited about space.

The question of humanity’s future relationship with space is more complex than just a simple “Will we settle space or not?” A government promising to under-regulate the private space industry is not the same thing as the promise of a bright future in space. We have to ask which universe we want our descendants to live in: the peace, curiosity, and diversity of Star Trek, or the cruelty and oppression of its Mirror Universe?

Of all the many lessons that Star Trek’s stories can provide about our future in space, this feels like the most relevant one for our present moment. The bad guys in the fictional mirror are not a made-up alien species: they are us. But so are the good guys. We have to decide (over and over again) which direction we want this story to go.

I will maintain that I think Final Frontier a much better film than is popularly remembered. It is great to have an exploration and adventure film with strong characters.

Excellent start, Erika. In fact when we look at the Star Trek Universe (from TOS to Strange New Worlds) there is a lot of topics to be explored. Spock would say: "Fascinating". I think that ST is like a desirable future but The Expanse is closer to our reality (exception to the protomolecule). There are some points I would like to add for discussion, if I may. The first contact with the Vulcans thanks to the first warp drive test by Cochrane was fundamental. They helped to expand human knowledge and technology but Vulcans had some control to what humans could do which was not approved by Jonathan Archer (the first Enterprise captain almost 100 years before Kirk). It is interesting to think that Cochrane developed the warp drive after WW III and the Eugenic wars (which I think deserves more detailed attention) when humans faced a kind of barbarian times. That is a timeline that could be more explored, I mean, how humans ended up with poverty and achieved a high level technological development. Today we have the famous Alcubierre's paper from 1994 but not the Physics required for a warp drive. That is another thing I use to compare ST and The Expanse. In fact we are closer to a fusion drive than a warp drive. The Prime Directive is something that we could use as an example today because it shows how important a regulation can be even if it appears to be too rigid in some cases. I am referring to regulations for AI, Biotechnology, for example.

What Roddenberry created is amazing and I hope that can be alive for 50 years more.

Looking forward for the next one, Erika! I loved it. Congratulations.