In July 1997, astronomer and geologist Gene Shoemaker (co-discoverer of the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet, which crashed spectacularly into Jupiter in 1994) was searching for meteor impact craters in central Australia when he was tragically killed in car accident. Shoemaker had always wanted to visit the Moon, and had at one point been considered as a potential Apollo candidate, but was disqualified for health reasons. So after his death, one of Shoemaker’s colleagues, planetary scientist Carolyn Porco, suggested that Shoemaker’s ashes be sent to the Moon, to honor his lifetime of studying space and his fascination with our closest celestial neighbor.

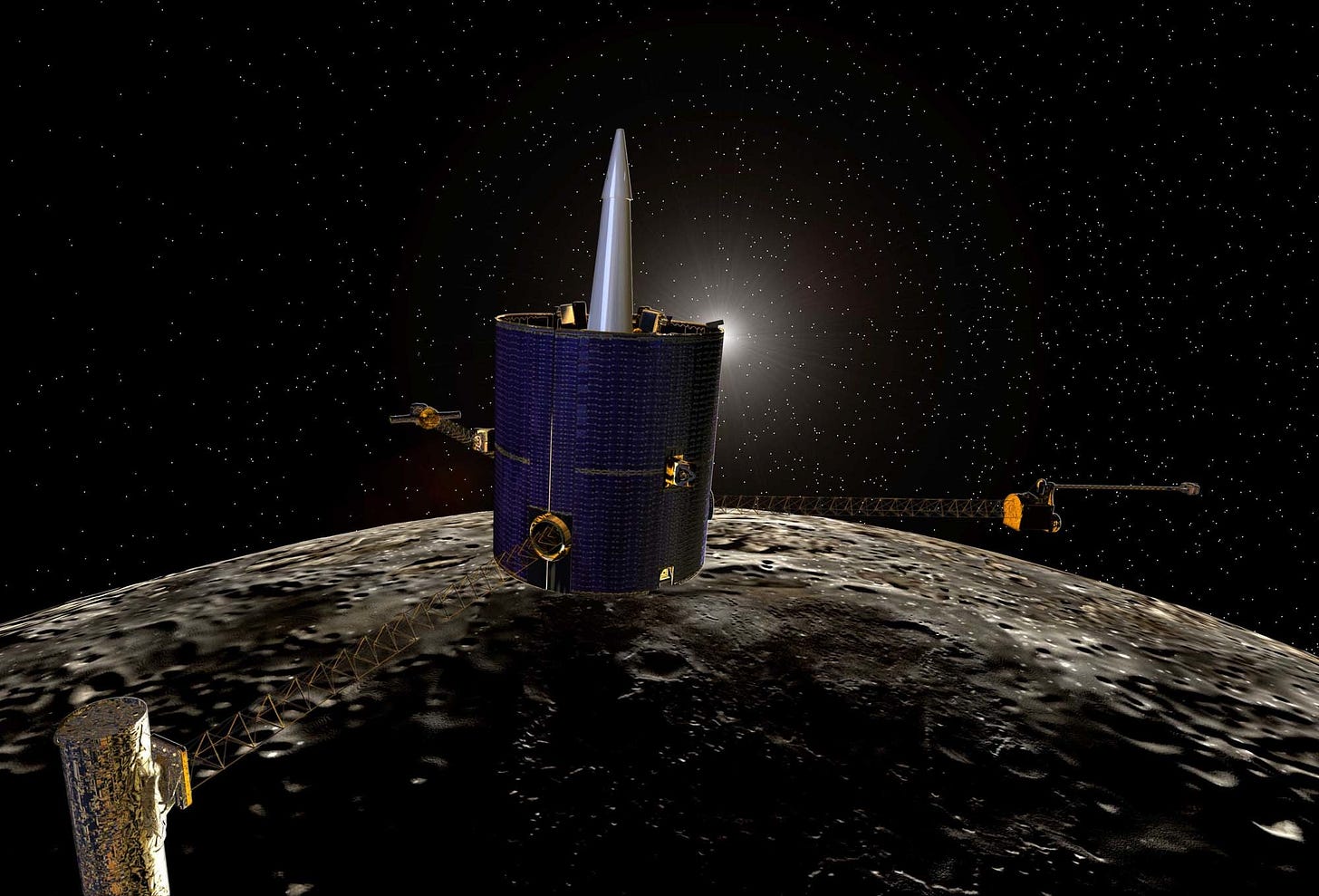

NASA agreed and contacted Celestis, a space burial company that had its first flight in April 1997, when it launched the ashes of 24 people, including Gene Roddenberry and Gerard O’Neill, into Earth’s orbit (where they remained until the Celestis spacecraft re-entered the atmosphere in 2002). Celestis agreed to build a capsule to carry an ounce of Shoemaker’s ashes on the Lunar Prospector mission to the Moon. The Lunar Prospector spacecraft orbited the Moon for a year and a half, mapping the lunar magnetic and gravity fields and the deposits of hydrogen on the surface. At the end of the mission, on July 31, 1999, the spacecraft (with the Celestis capsule attached) was deliberately crashed into a crater1 near the Moon’s south pole.

But after the Lunar Prospector was launched in January 1998, when it was announced that the mission would carry Shoemaker’s ashes to the Moon, NASA was surprised to find that this decision was deeply upsetting for some Indigenous groups who heard about it. Albert Hale, the president of the Navajo Nation at the time, explained that “The moon is a sacred place in the religious beliefs of many Native Americans,” and that “It is one thing to probe, the study, the examine and even for men to walk on the moon, but it is sacrilegious, a gross insensitivity to the beliefs of Native Americans to place human remains on the Moon.”

Gene Shoemaker’s widow, fellow astronomer Carolyn Shoemaker, was “completely astonished” by the controversy, because, as she noted, her husband felt so strongly about going to the Moon that “It’s almost a religious thing with him.” But the conflict, I think, is not about whether Gene Shoemaker had as much reverence for the Moon as the people of the Navajo Nation; it’s that different cultures have different (and sometimes contradictory) concepts of how land and human remains ought to be treated in order to properly demonstrate that reverence.

For example, cremation was historically forbidden by the Catholic Church, such that cremated Catholics were excommunicated and their remains were not to be buried in Catholic cemeteries, but more recently the official stance has shifted as cremation has become more popular than burial in many countries. Cremation is prohibited under Jewish law, which required the burial of the dead and forbids mutilation of the body. For Zoroastrians, both burial and cremation introduce corruption to the natural world, and many prefer to leave the body isolated but exposed to the elements, to be consumed by birds and animals.

So in some human cultures, sending the ashes of a loved one to the Moon can be seen as a physical representation and celebration of that person’s connection to the Moon. But in others, depositing human remains on the Moon desecrates a sacred place. This kind of conflict occurs on Earth, as well, which is why there are rules about where you can and can’t scatter ashes in public places like national parks or at sea.

After Albert Hale’s remarks about the Lunar Prospector, NASA apologized, and the NASA director of public affairs at the time, Peggy Wilhide, gave her “commitment that if we ever discuss doing something like this again, we will consult more widely and we will consult with Native Americans”. But will that commitment apply to space burial companies like Celestis, especially if they launch o private, non-NASA vehicles? NASA doesn’t need to be consulted for such missions, but the FAA must provide a launch license for space missions launched by U.S. companies. Will the FAA consider the complex concerns surrounding human remains on the Moon if a lunar burial company starts requesting authorization to send more ashes to the Moon? Or will ignorance and indifference result in more space burials by well-meaning and bereaved families that will be experienced as desecration by many cultures on Earth?

*This topic was brought up at the Artemis & Ethics Workshop that I attended a few weeks ago by Dan Hawk. I want to thank Dan, and the other participants who discussed this thoroughly throughout the workshop, for bringing this to my attention.

Other News

I’ll be attending the last two days of the National Space Society’s International Space Development Conference on May 27-28 in Frisco, TX. I’m giving a talk on the afternoon of May 28 as part of the Living in Space track— come say hi!

This crater was named Shoemaker crater in honor of Gene Shoemaker. An impact crater in Western Australia, formerly known as Teague Ring, was also named after him.

"Or will ignorance and indifference result in more space burials by well-meaning and bereaved families that will be experienced as desecration by many cultures on Earth?"

I think consideration of cultural differences is valuable if one respects the idea of democracy.

However, rights over lands and spaces beyond one’s home are as ridiculous as the current attempts at the appropriation of fetal rights by many American Christians.

This is not indifference to, or ignorance of, cultural rights — it’s a challenge to the idea that cultural rights or religious myths trump logic, reason, and science — as well as simple practicality.

The idea that a burial on the Moon is “desecration” because certain groups of people have incorporated a mythic conception of a celestial body into their culture … is as absurd as the idea of “blasphemy” in various religious dogmas.

How far would this idea of “desecration” go? Would it include Venus and the other planets visible in our sky — or to every other part of the universe? The whole idea is an affront to the Enlightenment, which to date is one of humanity’s greatest advances.

"and sometimes contradictory"

This is the crux of the issue since this is being cast as either insensitivity or unethical when instead it is an inherent incompatibility between cultures and their moral philosophies. There are many of us who feel a very deep moral imperative to fill the Universe with life and, in the case of life on this planet, with our death. People are going to go to the Moon, Mars, and far far beyond those. And they are going to take all of their cultural, moral, and ethical baggage with them. In some of those cultures they will want to bury their dead. One culture doesn't get veto the entire planet's access to and use of space.