What Can Spacesuits Learn from Phone Chargers?

Technology cross-compatible and space safety

If you’re reading this newsletter, you’re very likely aware that two NASA astronauts who traveled to the International Space Station for a one-week mission back in June will now be staying there through February due to a thruster malfunction in their Boeing Starliner spacecraft. Plenty of digital ink has been spilled so far about this situation, which has stoked the debate over Boeing’s vs. SpaceX’s approach to technology development and stimulated plenty of conversation about NASA’s safety decisions. Besides stating that I don’t envy any of the decision-makers here, and that I hope the astronauts have a safe trip home in February, I want to dive in to one particular technical challenge complicating this situation and its implications for the future of commercial spaceflight.

As NASA deliberated on whether to bring Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore back from the ISS in the Boeing Starliner they’d arrived in or in one of the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft that travels to the station more regularly, it was reported that Williams’ and Wilmore’s Boeing spacesuits are not compatible with SpaceX capsules. These aren’t the bulky, stiff spacesuits that astronauts wear during spacewalks, but the slimmer “launch and entry” suits that they wear during, well, launch and re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. While capsules are pressurized during trips to and from the surface, wearing launch and entry suits prepares travelers for a possible emergency loss of pressure (like the oxygen masks on airplanes, if airplanes traveled through the vacuum of space).

The problem is that launch and entry suits plug into the capsule, connecting the suit to the spacecraft’s electronics and software. And suits designed by different companies are not designed to be compatible with other companies’ spacecraft. So even though Williams and Wilmore brought their own launch and entry suits to the ISS on the Boeing Starliner, they wouldn’t be able to use them to, for example, catch a ride back to Earth on the SpaceX Dragon currently docked at the ISS, because the Boeing suits can’t be plugged in to the Dragon capsule. That doesn’t mean that they couldn’t evacuate the ISS on the Dragon in the event of an emergency on the station— astronauts can return to Earth “unsuited”— but this would carry an extra risk.

Ultimately, NASA decided to pull two of the four astronauts from the next planned flight to the ISS, which will be on another Dragon capsule. That flight will carry two empty SpaceX suits (and empty seats) for Williams and Wilmore, who will return home with the rest of that mission in February 2025.

So why aren’t launch and entry suits cross-compatible? There are some benefits to encouraging engineering companies to pursue different paths, especially in the early days of technology development. If NASA’s requirements for their commercial vendors were too strict, companies might not have the flexibility they need to innovate and develop the best possible technologies. And if a major flaw were found in one company’s suit technology, parallel development of alternative approaches by other companies would ensure that NASA’s human spaceflight goals are not significantly delayed by such a finding. So currently, NASA does not require that suits from different spacecraft be cross-compatible.

But as this incident demonstrates, incompatibility in space technology isn’t just inconvenient; it can be a threat to crew member safety. I’ve often heard space ethicists recommend regulations requiring universal compatibility in technologies like spacecraft docking rings to ensure that space traveler safety is not jeopardized for the sake of business interests. In the more distant future of commercial space travel, non-compatibility might eventually be motivated not by the pursuit of innovation but directly by the pursuit of profit.

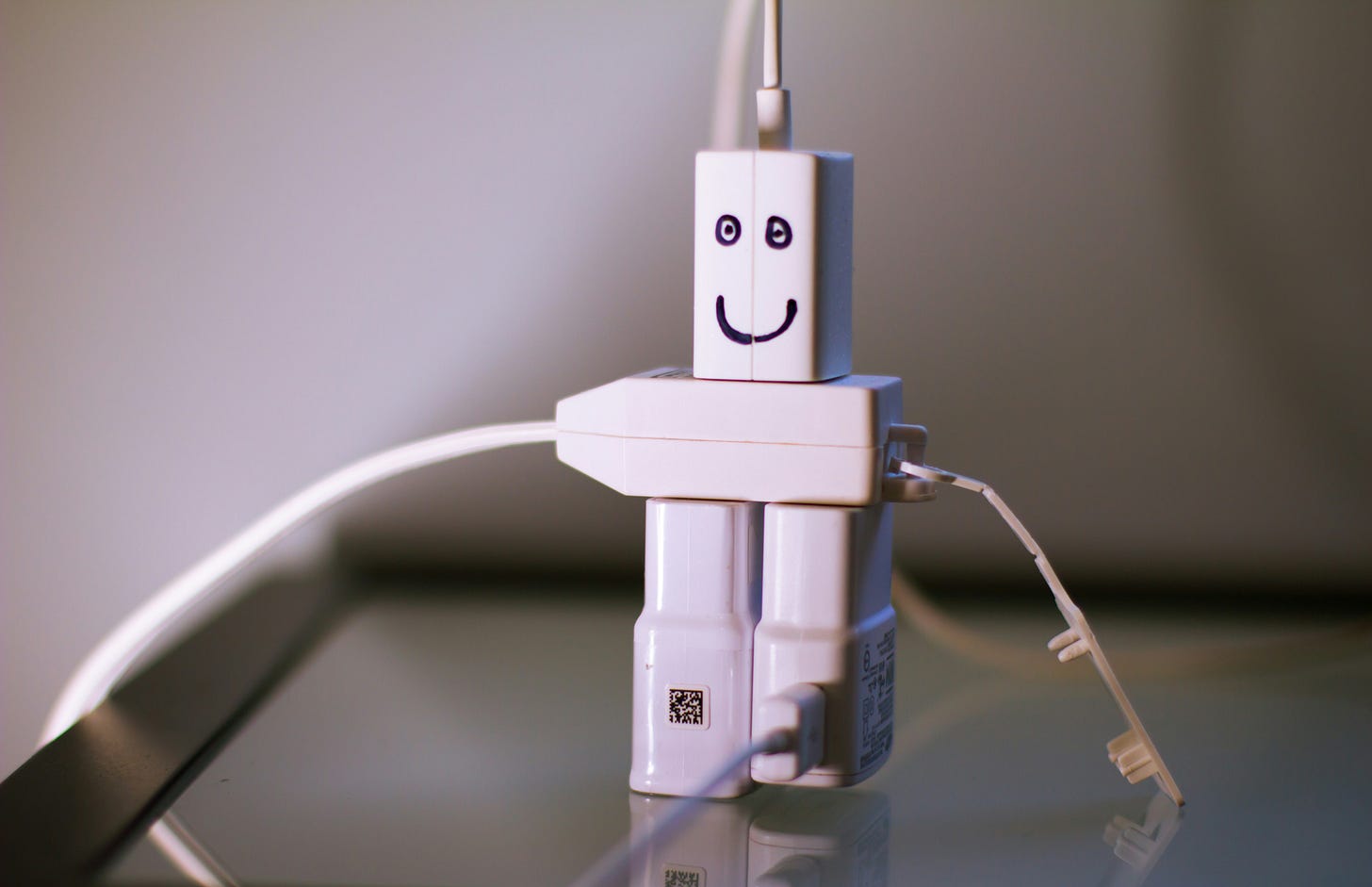

Consider, for example, the recent legal battle over compatibility in a much more terrestrial technology: phone chargers. Apple has been using a proprietary charging port for the last several versions of the iPhone: the Lightning connector, which is incompatible with the more widely used USB-C. There are various historical reasons for this, but one benefit for Apple is that iPhone customers buy their charging cables (and a pile of adaptors) from Apple rather than joining the larger market for USB-C chargers. A 2022 European Union law, however, requires that all devices sold in the EU be USB-C compatible by the end of this year. The EU argues that this will reduce electronic waste and save consumers money; Apple argues that it will stifle innovation. But losing the European market would be a huge blow, so Apple switched to a USB-C port for the new iPhone 15.

Now imagine, a few decades from now, a company selling luxury space capsules that requires customers to purchase their proprietary luxury launch and entry suits, which happen to be incompatible with standardized (but not legally required) suit/capsule connections. Sure, this would allow the company to experiment with their own suit features (maybe a minibar?), and perhaps charge a premium for their name-brand suits. But in an emergency— say, a spacecraft malfunction requiring rescue and transfer to a different type of craft— the customers could be left without the safety benefits of the suits. Technological incompatibility is inconvenient and expensive when it comes to phone chargers, but it could be life-threatening in space travel.

NASA is not responsible for regulating the commercial spaceflight industry; they’re just the industry’s biggest customer right now. And they’re facing a lot of tough choices as they explore commercial options for human spaceflight. Hopefully, national and international policymakers—as well as the industry itself— recognize this as an opportunity to consider how to balance the benefits of unregulated innovation with the need to prioritize the safety of space travelers.

Other News

I’ll be delivering a keynote at a conference on Social and Ethical Frontiers in Space Exploration in Kiruna, Sweden later this month.

My panel with Kelly Weinersmith, Shawna Pandya, and Pat Remias at the ASCEND conference last month is now available online here: